The Death of Design

A quiet eulogy for what design used to be

Last week, Dribbble—the once-quintessential platform for designers—introduced new terms requiring all client interactions, and payments, to happen exclusively on their platform.

It didn’t go down well.

Dribbble helped grow careers. Now, designers can’t even link to a portfolio, a social handle, or an email address. It doesn’t just feel backwards—it feels like a philosophical betrayal of what made it great.

But if we’re being honest, this didn’t come out of nowhere. It feels like design communities have been fading for years.

Not because Dribbble sawed off the branch it sat on—but because design withered.

I started designing before visual design matured into the massive industry it is today. Before the proliferation of design tools. Before design became systemised at scale.

It was around 2008 or 2009. Photoshop was king. iOS had just launched. The App Store was exploding. Everything felt new, and no one really knew what they were doing—including me. But that was part of the magic.

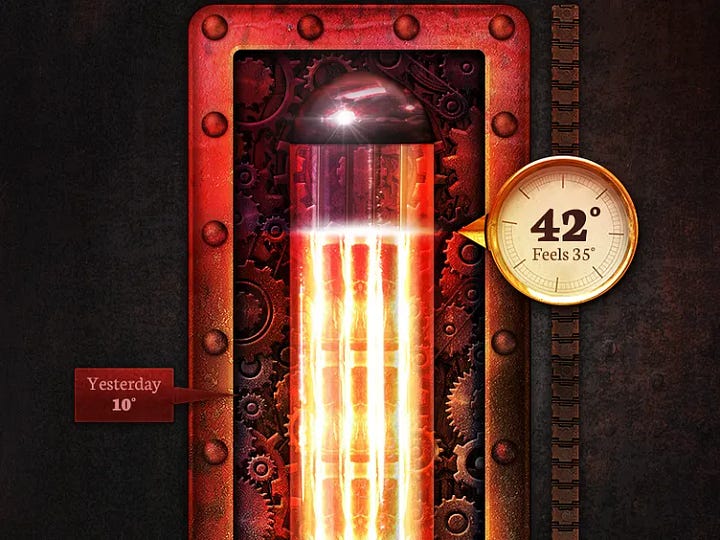

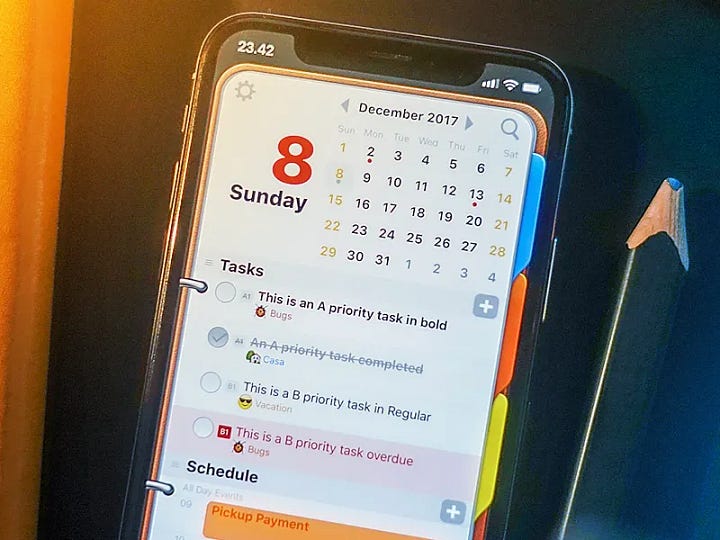

We designed things just to see what they might look like. A calendar app, a music player, a weather app made of chrome and glass. Were they practical? Not always. But they were fun. And expressive. And strangely personal. We shared them on Dribbble, rebounded each other’s shots, iterated, and played.

I remember spending hours on the tiniest details of an interface element no one had asked for. Just… exploring. Pushing pixels for the sake of it. The tools I had didn’t dictate the results—and the community I found on Dribbble was open, curious, and encouraging.

In the early 2010’s, a new generation of designers was entering the scene—many of them coming out of design schools, trained with fresh tools and frameworks that reflected a more modern, streamlined industry. Job titles that had previously just been ‘designer’ multiplied into subcategories—UI designer, UX designer, product designer. Each with its own rules, processes, and expectations. The tools they used were faster, more specialized, and more focused on efficiency. But with that came a certain sameness. The more we streamlined the process, the more we streamlined the output. In a way, we designed ourselves into conformity.

Minimalism took over.

We stripped out the texture, the depth, the weird little quirks that made things interesting. Suddenly everything had to be flat, neutral, quiet. White space became the design. Personality took a backseat to consistency. And over time, the mess—the fun—was sanitized away.

And somewhere along the way, that kind of design—the playful, expressive, emotional kind—started to wither. It might sound dramatic to say it died—but in many ways, it did.

That spirit of design was pushed to the edges, quietly replaced by something more uniform, more predictable. Apps, websites, even branding, all started to look very similar.

To be clear, design has grown in meaningful ways. It’s more accessible, more collaborative, more inclusive than it used to be. We’ve built systems that help teams scale, ensured our work reaches more people, and embraced principles like accessibility and usability in ways the early design days didn’t always consider. That maturity matters. But in the process of growing up, we lost some of the rawness—some of the spirit that made design feel like a creative playground.

I feel incredibly lucky that I learned design in a time before the rules were written. It taught me to be curious, to take risks, to find meaning in the making. It showed me that design could be personal—that it could be play. And that play was more than enough.

I hope new designers find their own version of that freedom.

Dribbble closing itself off feels like a final, quiet confirmation of what many of us already knew: that something beautiful faded while we were busy optimising for efficiency. While we streamlined. Systematised. Professionalised.

But maybe that’s also the reminder we need.

That it’s on us to make space again—for weirdness, for personality, for joy. To choose tools that invite play. To build communities that spark creativity—not manage it.

Because if something beautiful really did die, then we owe it to ourselves—and to the next generation—to bring it back to life.

Sponsor

Elements is a modern web design app for macOS powered by Tailwind CSS. Whether you’re prototyping or publishing, Elements gives you full control with a visual editor. Build with production-ready dev components, get instant previews, and stay up to speed with weekly updates and dev diary videos. It’s the perfect tool for developers and designers building websites visually.

Use code FLARUP at checkout and get 10% off your purchase.

You too can sponsor this newsletter and get in front of thousands of designers, makers, and curious minds. → Learn more.Nice Things

Excitedly waiting for my Analogue3D.

I’m kinda fascinated by the Vibe Coding Game Jam.

Bitmap Books make some of the most visually stunning books on gaming history. I adore the ones I have and always follow their latest releases.

Thank you for reading.

All of this perfectly complies with the development rules of the Internet. In the early days of the Internet, everyone had unprecedented possibilities for individual expression, but as the Internet expanded and integrated into every corner of life, we found that individuality was increasingly dissolved and everyone's voices were increasingly converging. The initial Internet encouraged individuality, but the expanding and ubiquitous Internet eliminated individuality. The same is true for design.

I wonder if the field of design would be completely unrecognizable to us if we traveled in time to before the Internet. I started working in 1996 and I thought design was the place to be. But then all these other titles took the spotlight: UI, UX, Product, etc. So maybe design is maybe closer in relevance to the world today as it was in 1990.